I cut my literary teeth on Graham Greene.

I cut my literary teeth on Graham Greene.

Brighton Rock was the first ‘serious’ novel of my own choosing which I connected with – which had complex characters I could both identify with and distance myself from at the same time; which had a plot and themes that have resonated down the years.

I was in the 4th year at school – so would have been around 15 years old.

Over the next 10 years I read with increasing understanding nearly everything Greene had written in novel form – and he formed the basis, along with George Orwell, of my model modern – of the real story teller.

Yes, I also did the classics and the very moderns – dutifully plodded through Elliot and Dickens; tackled the Woolf (she won the first couple of rounds – only after having to teach her did I finally understand how brilliant she was); ignored Golding – he had been a compulsory read at school so was off the ever return to - again, ‘til I had to teach him – and his star rose.

I did the Irish – and went international, with the French – dipped into some drumming Germans and swung back to the origins of the English novel – a Sterne warning to all. Sneered at the North Americans – marvelled at the South Americans – and, like generations past and to come, wondered what all the Quixotic fuss was.

All the time, Greene formed images – the whisky priest, American agent, and English agent; Third Men and the Quiet Men – Vietnam and Central Africa; the Caribbean and London sub-urb.

And then I finished with him – moved on.

About three weeks ago I picked up ‘The Heart of the Matter’ – Greene’s novel of 1948 set in West Africa during the Second World War.

About three weeks ago I picked up ‘The Heart of the Matter’ – Greene’s novel of 1948 set in West Africa during the Second World War.

It has everything I remember – but a lot more.

Perhaps because I’ve been working on ‘The Taming of the Shrew’ at the same time – elements of religion, marriage and identity have stood out in focus in a way I don’t remember. The Shrew is a play all about seeking salvation through appropriate partnering – The Heart of the Matter, how salvation is individual and not to be found in others.

This was a pretty dismal, depressing read the first time – it touched on the meaning of existence and right way to live – on lovelessness and the unforgivable: What I hadn’t tasted then was the existential angst, the deepness of the despair and the strength of individual choice.

Major Scobie, our everyman, is a policeman with a wife – respectability personified. He is hated by the ex-pats because he isn’t corrupt – and loved by the Syrian dealer in corruption for the same reason. His lack of corruption perversely makes him untrustworthy to his own kind – and his career suffers as a consequence. The only true friendship comes from the Syrian, Yusef – very not British – and it is a friendship Scobie can never accept.

It is Scobie’s fall from grace we follow – in the true meaning of the words: He is not ruined in any earthly way – but his spiritual existence is, at least in his own mind, spiraling ever further down through the circles of hell.

In one of the more frighteningly understandable images of the book, Scobie sees himself as fisting god – not fighting in the abstract, but physically punching and damaging the flesh: It is an image which horrifies in its very physicality – and in the clarity of self-knowledge Scobie exhibits.

Around this dying light flutter a whole cast of shadow-dwelling characters.

Scobie’s wife is damaged goods – her husband’s incorruptibility has driven her to this god forsaken land so she has plunged into the superficialities of Catholic dogma – the ritual and the literal making her empty life fuller. She reads books and poetry – replacing any real inner life with printed words and borrowed sounds.

She is not a fool – but it is her needs that keep what is left of their marriage alive – most of it died with a young daughter back in England. Her leaving to live in South Africa opens the gap needed for a replacement ‘needer’ – and the final human dilemma that shatters Scobie’s relationship with the divine.

Wilson, spy-on-his-own-kind, and writer of trash poetry; driving Scobie no more than a mosquito could - tolerated as a fact of the environment – in ‘love’ with Scobie’s wife and emptying the word of all depth.

Helen, fallen woman and siren – who is no more than a vessel the fates use to trap Scobie – from her very first appearance as love-less, dried-skin of a girl clutching a stamp-album to near-whore for the ex-pat wild boy.

A priest who knows he serves no one well – least of oll Scobie; a priest who needs to confess as much as to listen to confession – but perhaps the only one who sees the real relationship of Scobie to his god – who appreciates the complexities and ultimate unknowability of any meaning in life.

These moths flicker in and out of the life that is Scobie – contrasting their weaknesses with the immense strength he is using in his ‘psychomachia’ – his soul-struggle.

Scobie is ultimately heroic – in his choice and in facing of the consequences of that choice. He is very much a 20th Century man – having both the consciousness and anxiety William Golding identified as hallmarks in the work of Graham Greene.

Technorati Tags:

Graham Greene,

Heart of the MatterPowered by ScribeFire.

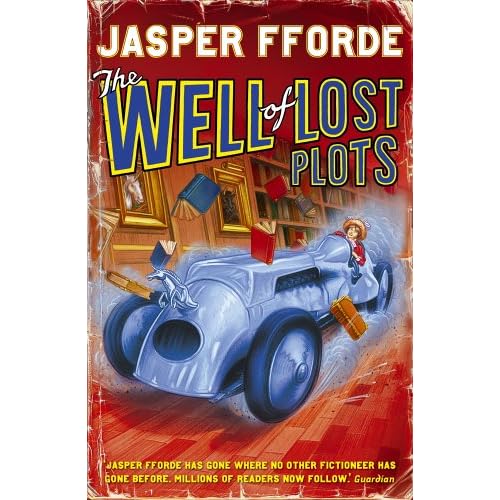

To loose the plot of something is to go a little crazy to be totally out of touch – I’m not suggesting Mr. Fforde has gone that far, but the plotting of the story does suggest a little desperation and there are a couple of details that add to an inconsistency that is not comfortable for the reader.

To loose the plot of something is to go a little crazy to be totally out of touch – I’m not suggesting Mr. Fforde has gone that far, but the plotting of the story does suggest a little desperation and there are a couple of details that add to an inconsistency that is not comfortable for the reader. I cut my literary teeth on

I cut my literary teeth on  About three weeks ago I picked up ‘

About three weeks ago I picked up ‘